LOADING

Methodology

Overview

Summary

Following the development of the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI), we wanted to further investigate environmental externalities attributable to the Bitcoin network, more specifically, the impact Bitcoin has on climate change. In recent years, the debate around Bitcoin's sustainability has gained momentum as cryptocurrencies have risen in popularity. So, by adding this new index to the CBECI, we hope to contribute to the debate and offer an approach to quantify the environmental impact.

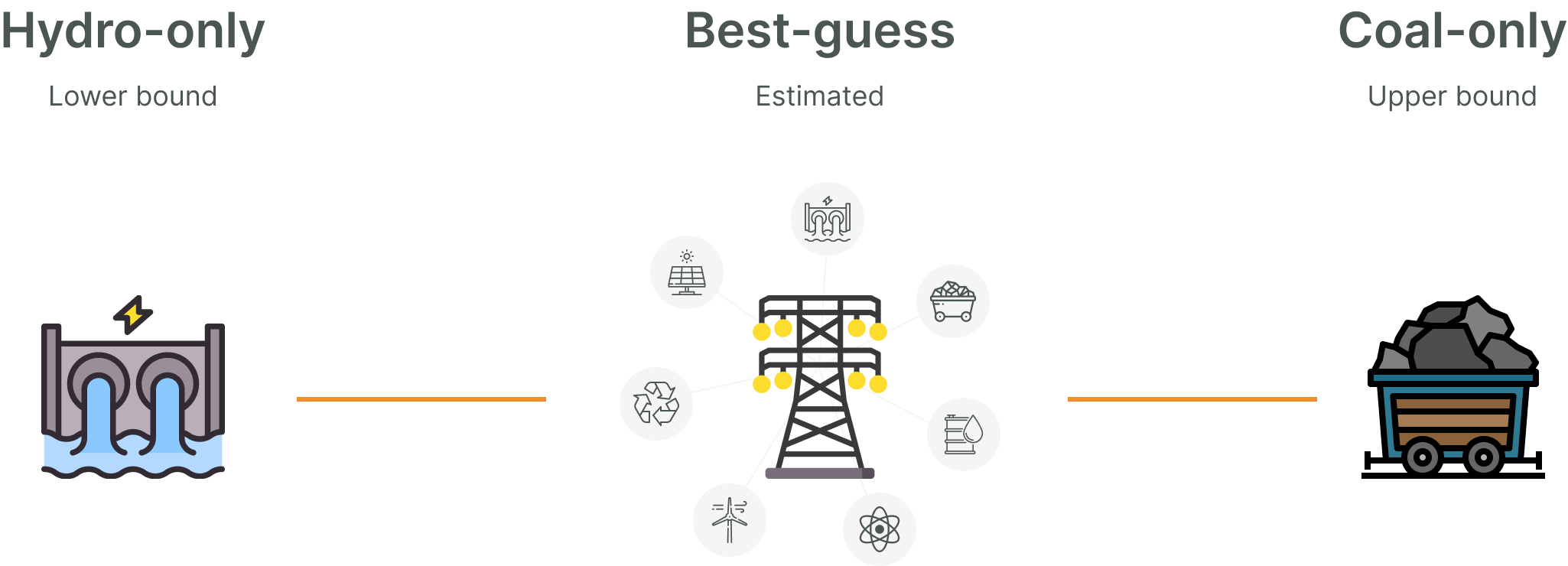

This issue was looked at from multiple angles and, using similar logic to that behind the CBECI, a sensitivity analysis was performed to identify how greenhouse gas (GHG) emission estimates change as key parameters are altered. Since exact GHG emissions cannot be determined, a hypothetical range consisting of three scenarios is used, two of which form the upper and lower bounds. Within these limits is the best-guess estimate, which represents a more realistic view of Bitcoin's actual GHG emissions.

In this study, the hydro-only scenario (lower bound) is the most environmentally friendly of the three estimates and assumes that all Bitcoin miners use only hydropower. The coal-only scenario (upper bound) is the least environmentally friendly estimate and assumes that all Bitcoin miners use only coal power. The best-guess estimate is based on a more sophisticated approach that leverages additional data on geographical hashrate distribution to differentiate between energy sources used by different countries (or provinces or states) to generate electricity.

This study's main purpose is to provide a daily annualised (ann.) estimate of the Bitcoin network's GHG emissions. However, due to the lack of data during specific periods, our approach had to be divided into three intervals. These intervals are explained in more detail in later sections. Additionally, our aim to provide daily estimates requires multiple data sources that are continuously updated and available at different frequencies, either on a daily, monthly or yearly basis. This problem is partly addressed by creating clearly defined intervals for periods when no mining map data is available. Another problem is the uneven frequency with which data on electricity mix profiles is reported. Therefore, it was decided to always use the most recently available data for each country, province or state. However, when new data becomes available for a given year, the estimate for the period is adjusted retroactively.1

It is also important to note that this index only considers the environmental impact associated with the electricity consumption of Bitcoin mining and, therefore, cannot be considered a life-cycle assessment. This simplification is based on research conducted by Köhler & Pizzol (2019), who identified geographical distribution and hardware efficiency as the main factors influencing the total environmental footprint, while other factors only had a minor impact (<1%).

Key terms

Table 1: Introduction to key terms and abbreviations

Term | Explanation |

(Mt) CO2e (Million tonnes) carbon dioxide equivalents | The CO2 equivalent emissions are based on their 100-year global warming potential (GWP100). Other GHGs are converted to an equivalent amount of carbon dioxide. |

ann. Annualised | Annual emission estimate based on daily emission estimate. It is assumed that the daily emission value remains constant for 365.25 days. |

Emission intensity | Life-cycle emissions of electricity generation technologies are given in gCO2e/kWh. |

Electricity mix | The electricity mix shows the share of the respective primary energy sources in total electricity generation. These include coal, oil, gas, nuclear, hydro, solar, wind and other renewables, as defined in Table 3. |

gCO2e/kWh A gram of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions per kilowatt-hour | The measurement of the environmental impact of one kilowatt-hour in carbon dioxide equivalents |

GHG Greenhouse gas | Carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and fluorinated gases |

Model parameters

Table 2: GHG index model parameters

Parameter | Description | Source |

Estimate of annualised electricity consumption (best guess) | Estimated annualised electricity consumption of the Bitcoin network | Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance. Available at: https://demo.ccaf.io/cbeci/index |

Mining map | Geolocational data of Bitcoin mining operations | Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance. Available at: https://demo.ccaf.io/cbeci/mining_map |

Life-cycle emission factors for electricity generation technologies | As illustrated in Table 3 | National Renewable Energy Laboratory. (2021). Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Electricity Generation: Update. Golden: NREL |

Share of electricity production by source | Determining the most recent electricity mix of all countries for which data is available | Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2020). Energy [online] OurWorldInData.org. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/energy BP Statistical Review of World Energy. Available at: https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy Ember Global Electricity Review (2022). Available at: https://ember-climate.org/insights/research/global-electricity-review-2022/ Ember European Electricity Review (2022). Available at: https://ember-climate.org/project/european-electricity-review-2022/ |

Sources of electricity generation by province | A list of the different energy sources used for power generation in Chinese provinces | National Bureau of Statistics. Available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/ |

Sources of electricity generation by state | A list of the different energy sources used for power generation in US states | US Energy Information Administration. Available at: https://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/state/ |

Life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions from electricity generation

Table 3 lists the median total life-cycle emission factors (one-time upstream, ongoing combustion, ongoing non-combustion and one-time downstream) for selected electricity generation technologies. The values are based on a systematic review of published life-cycle assessment (LCA) studies conducted by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (2021).

Table 3: Life-cycle emission factors for electricity generation technologies

Electricity generation technology | Life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions (gCO2e/kWh) |

Coal | 1,001 |

Oil | 840 |

Gas | 486 |

Nucleara | 13 |

Hydro | 21 |

Solarb | 35.5 |

Windc | 13 |

Other renewablesd | 32.3 |

a Light-water reactor (including pressurised water and boiling water) only, b Mean value of photovoltaic (thin film and crystalline silicon) and concentrating solar power (tower and trough), c Land-based and offshore, d Mean value of geothermal, biomass and ocean.

Methodology

This section briefly outlines the core concept of our methodology before delving deeper into how the estimates are calculated.

Structurally, this study follows a similar approach to the CBECI by introducing hypothetical lower and upper bounds that form the range of estimated GHG emissions. This is the basis of the sensitivity analysis, which is summarised in Figure 1. The two limits are outlier scenarios based on the abstract assumption that all the electricity used is generated by a single energy source (coal-only or hydro-only). This format is simply illustrative and provides context to make interpreting the results more intuitive. In reality, the electricity used is generated by a mix of energy sources (the electricity mix). Knowing the composition of this mix is essential to computing the emission intensity associated with the Bitcoin network. In this study, the emission intensity serves as a measurement of GHGs emitted per kilowatt-hour, given as gCO2e/kWh. Table 3 lists all the energy sources used in this study with their respective emission intensities.

Figure 1: Sensitivity analysis

While the emission intensity remains constant for both outlier scenarios, as only one energy source powering the Bitcoin network is assumed, the best-guess estimate accounts for all the energy sources in Table 3. This presupposes an understanding of which energy sources are used and to what extent. Therefore, determining the emission intensity of the entire Bitcoin network requires data on the relevant geographical locations of the mining facilities from which the computing power (hashrate) originates and their electricity mix.

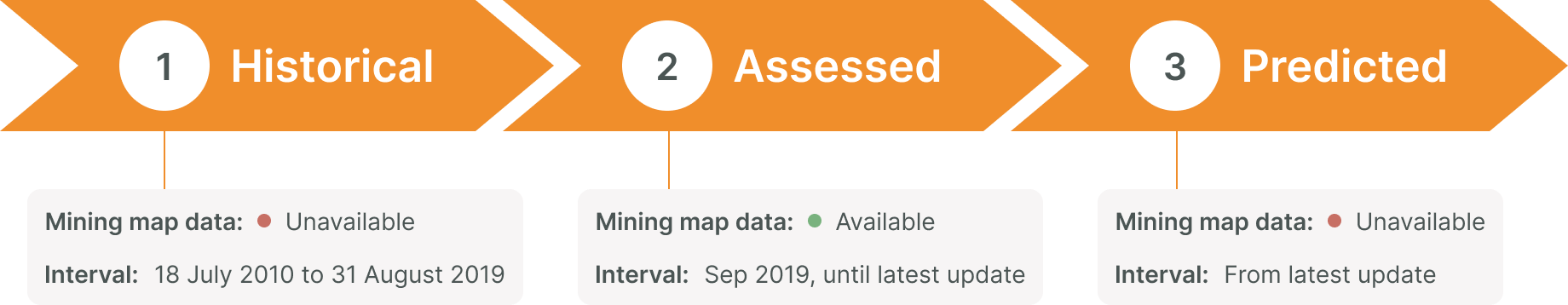

Besides showing a range of estimates given different assumptions on the energy sources used, a solution had to be found to deal with periods for which information was unavailable. As mentioned previously, the geographical location of mining facilities is vital to determining the electricity mix. However, data on the geographical distribution of hashrate only started to be collected in September 2019 and is available only until the most recent update of the mining map. Therefore, a solution had to be found for the period before data became available, and for the months for which data was not yet available. To address this challenge, ann. GHG emission estimates are calculated for three different time intervals – historical, assessed and predicted – as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Time intervals

The issue of unavailable data during certain periods only applies to the best-guess estimate, since the upper- and lower-bound estimates are based on a single energy source (coal-only or hydro-only) and, hence, changes in geographical hashrate distribution do not impact the emission intensity. By assuming a single energy source, the emission intensity stays constant over time and always corresponds to the value in Table 3, regardless of where the hashrate originates.

For the best-guess estimate, depending on the time interval, different approaches had to be developed to estimate GHG emissions. The estimates for the historical and predicted intervals are based on major simplifications, while computing estimates for the assessed interval is more complex:

The historical interval assumes that Bitcoin mining operations are distributed proportionally across the world, based on each country’s share of total global electricity production.

The assessed interval allows for much greater granularity as, during this period, data on global hashrate distribution is available monthly.

The predicted interval assumes that the most recent mining map update is still a valid approximation of the current hashrate distribution.

The assumptions that underpin each interval have significant implications for the estimated emission intensity during that interval. As illustrated in Figure 3, the emission intensity fluctuates only slightly during the historical interval and remains constant during the predicted interval. However, when global or regional changes in Bitcoin mining activity are considered, as they are in the assessed interval, much greater fluctuations in emission intensity become visible. A more detailed explanation of these assumptions, including the calculations for all our estimates, is provided in the following sections.

Figure 3: Emission intensity based on Bitcoin electricity mix

Upper- and lower-bound estimates

In the upper-bound scenario, it is assumed that all the electricity consumed by Bitcoin miners is generated by coal. In the lower-bound scenario, the assumption is that all the electricity is generated by hydropower. Therefore, the emission intensities of the upper- and lower-bound estimates always equal the emission intensity of the relevant energy source (set s), as shown in Equation 1.

Because it is assumed that a single energy source is used, keeping (Is,d) constant, it naturally follows that changes in the geographical locations of mining operations, that would otherwise alter the network's electricity mix profile and thus change the emission intensity, do not influence ann. GHG emissions.

Best-guess estimate

Creating the three intervals

This section describes the three intervals in more detail and the reasoning behind creating them. As mentioned previously, these intervals were created to overcome the issue of data unavailability for certain periods.

First, it is important to highlight a key element that must be considered in the research, namely accounting for the dynamic nature of the Bitcoin mining industry and, specifically, the industry's ability to quickly relocate mining operations within or outside a host country. Being able to account for this dynamic nature is critical, as the location of operations determines the electricity mix profile in the model. Noteworthy are the seasonal migrations within China that demonstrate the importance of this matter, as evidenced in a later section by the severe variations in the country's emission intensity factor during the period for which regional data was available.

Each of the three intervals created – historical, assessed and predicted – uses a different approach to calculating the best-guess estimate. The historical interval addresses the unavailability of geolocational data before September 2019 – the first data point provided on our mining map. The assessed approach provides the most comprehensive estimate, as geographical hashrate distribution data is available for this interval. However, our most recent mining map data might not represent the current status quo. For example, our most recent mining map data could be as of January 2022, but several months may have passed since that date. This creates a potential gap between the current date and the most recent data available. Since the intention is to provide daily estimates, a new assumption was required to fill this gap, namely that there has been no change in the global hashrate distribution since the last data point in our mining map. This period is the predicted interval. However, it is important to note that this interval should be viewed with caution. The reason for this is outlined in more detail in the section on the predicted interval.

Historical interval

The scope of this study would have been considerably limited if only the period for which data was available was considered. Hence, the historical interval was established to account for the absence of mining map data from 18 July 2010 to 31 August 2019, and an alternative approach was created to approximate GHG emissions before 1 September 2019.

Given the above assumption, the estimated ann. GHG emissions (Gd) can be computed using Equations 2 and 3.

and,

Assessed interval

The assessed interval provides an ann. estimate of GHG emissions for the period between 1 September 2019 and the last day of the month for which mining map data was available. This interval represents the most comprehensive part of our work on Bitcoin's GHG emissions.

While the historical interval estimate is based on the simplified assumption that the world electricity mix is an accurate approximation of how the electricity consumed by Bitcoin miners globally is generated, the assessed interval accounts for differences in the electricity mix at a country, state or provincial level. This is done by applying a multi-step procedure that segregates countries with a known hashrate into the four categories shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Country categories

Category | Countries and jurisdictions |

1 | All countries and jurisdictions not mentioned in categories 2–4 |

2 | China |

3 | The United States |

4 | The set of countries and jurisdictions listed in Appendix 2 |

Segregating countries into different categories is necessary since location-specific peculiarities need to be considered. Category 1 consists of countries (listed in Appendix 1) for which the hashrate distribution is unknown, as opposed to China and the US (categories 2 and 3, respectively), for which more detailed information is available. For countries in category 4 (listed in Appendix 2), either the electricity mix is not available on a country level, or their associated hashrate is likely being inflated.2 The following sections provide a more in-depth description of the four categories.

After calculating the estimated ann. GHG emissions of each country (Gc,d) in the four categories, the country GHG emissions are aggregated to form the GHG emissions that can be attributed to Bitcoin (Gd), as shown in Equation 4.

Categories 1 and 4

As described below, the associated electricity mix profile is used for countries belonging to category 1, while an alternative approach has been adopted for countries falling under category 4.

Equation 5 shows the calculation of country-specific GHG emissions. Each country's emissions (Gc,d) are determined by multiplying the country-specific emission intensity (Ic,d) by the country's share of total electricity consumption (Ec,d). This approach ensures that regional differences in the emission intensity of power generation and Bitcoin mining activity are considered.

While Equation 5 is used for countries in both categories 1 and 4, the equation used for calculating country-specific emission intensities (Ic,d) differs.

For each country in category 1, the emission intensity (Ic,d) is calculated using the country-specific electricity mix profile. Hence, the value of each country's emission intensity is based on the energy sources used to generate electricity. The share of each energy source (Sc,s), derived from the electricity mix of every country, is multiplied by the corresponding emission intensity (Cs) of that source. The weighted emission intensities of all sources are then aggregated to form the country's distinct emission intensity (Ic,d), as illustrated in Equation 6.

For all countries that fall under category 4, no distinct emission intensities are computed. In this category, country-specific electricity mix profiles are assumed to equal the world electricity mix profile, thus, Ss,c,d = Ss,d. Consequently, the emission intensity (Ic,d) of all these countries equals the world emission intensity, as shown in Equation 7.

Besides examining the differences in country-specific emission intensities, it is also important to distinguish between the scale of Bitcoin mining activity in each country. To accomplish this, the electricity consumption associated with Bitcoin mining in each country (Ec,d) must be determined. As illustrated in Equation 8, this value is computed by multiplying each country's share of the total hashrate (Hc,d) by Bitcoin's total ann. electricity consumption (Ed).

Category 2

The additional information available on geographical hashrate distribution in China allows for a much more granular approach than for countries in categories 1 and 4. Using province-based data was particularly important in capturing seasonal relocations of Bitcoin miners within the country. By relocating from thermal-powered regions to those where hydropower was abundant, opportunistic miners took advantage of favourable electricity rates during the rainy season, when water levels rose. When the dry season arrived and the water levels dropped, miners returned to areas dependent on thermal power. This dynamic within the country consequently significantly altered GHG emissions associated with Bitcoin mining, depending on the season.

On that note, it is important to mention that provincial data is only available for the period between September 2019 and June 2021. Since the government-mandated ban in June 2021 on cryptocurrency mining, no provincial data has been available. However, despite this legislation, Bitcoin mining resumed in China shortly thereafter. Nevertheless, the ban caused miners to seriously consider the trade-offs between maintaining operations and the risk of being discovered.3

Given the logistical steps involved in relocating mining operations and the resulting increased risk of detection, it is assumed that if provincial data is not available, relocations have ceased and, until provincial data is available, any remaining Bitcoin mining activity detected on a country level is evenly distributed across China.

That being said, for the period where provincial data is available, the equation for calculating country-specific GHG emissions (Equation 5) had to be modified to account for this additional data. Equation 9 now follows the same logic as Equation 4 but, rather than aggregating country-level GHG emissions, province-specific GHG emissions are aggregated to determine GChina,d, as shown below.

Province-specific GHG emissions (Gp,d), in turn, are determined by multiplying the emission intensity of each province (Ip,d) by the provincial share of China's total electricity consumption (Ip,d), as illustrated in Equation 10. This accounts for differences in mining activity between different provinces.

Further, differences in the electricity mix of each province also need to be considered. As shown in Equation 11, this was accomplished by multiplying the share of each energy source (Sp,s,d), derived from the electricity mix of each province, by the corresponding emission intensity (Cs) of that source. The weighted emission intensities of all sources are then aggregated to form a distinct emission intensity for each province (Ip,d).

Besides examining differences in province-specific emission intensities, it is also important to distinguish between differences in the scale of Bitcoin mining activity across provinces, as this is essential for capturing the impact of the season-based relocations, as shown in Figure 3. This is done by determining the electricity consumption associated with Bitcoin mining for each province (Ep,d), as shown in Equation 12.

For simplification, it is assumed that China is divided into nine regions: Sichuan, Yunnan, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Beijing, Gansu, Qinghai, Shanxi and 'other provinces'. The electricity mix profiles of all these regions, apart from 'other provinces', correspond to their actual ones. 'Other provinces' is an artificially created region that functions as a proxy for all Chinese provinces other than the eight actual provinces named above. This is a workable simplification as the eight actual provinces account for most of the hashrate. This, however, required the electricity mix and hashrate share for 'other provinces' to be defined as no actual data is available for this region.

To isolate the hashrate share of 'other provinces' (Hp = other provinces), the sum of hashrate shares of all provinces, where p ≠ 'other provinces', is deducted from the total, as given by Equation 13.

To solve the problem of defining a dedicated electricity profile mix for 'other provinces', the national electricity mix of China was used as a proxy. Thus, the electricity mix profile of 'other provinces' equals that of China’s, as shown in Equation 14.

Category 3

The data available for the United States also allows for a more granular approach than for countries in categories 1 and 4. With update v1.2.0 of the CBECI, a regional mining map dedicated to the United States was added to the website, which provides information on hashrate distribution within the country. Knowing each state's share of the overall US hashrate allows Bitcoin mining activity to be matched with the appropriate electricity mix profiles.

However, state-level hashrate distribution data is only available from December 2021. Thus, an alternative approach had to be chosen for the period before this more granular dataset became available. Consequently, for the period before December 2021, the same approach used for countries in category 1, shown in Equation 5, was used for the United States. From December 2021, Equation 15 is used.

The state-specific GHG emissions (Gp,d) are determined by multiplying each state's emission intensity (Ip,d) by that state's proportional electricity consumption (Ep,d), as illustrated in Equation 16. This accounts for differences in the mining activity and electricity mix in each state.

To account for differences in the electricity mix, the share of each energy source (Sp,s,d), derived from the electricity mix of each state, is multiplied by the corresponding emission intensity (Cs) of that source. The weighted emission intensities of all sources are then aggregated to form the distinct emission intensity of each state (Ip,d), as shown in Equation 17.

In addition to examining differences in state-specific emissions intensities, it is also important to distinguish between differences in the scale of Bitcoin mining activity across states. This was done by determining the electricity consumption associated with Bitcoin mining in each state (Ep,d), as shown in Equation 18.

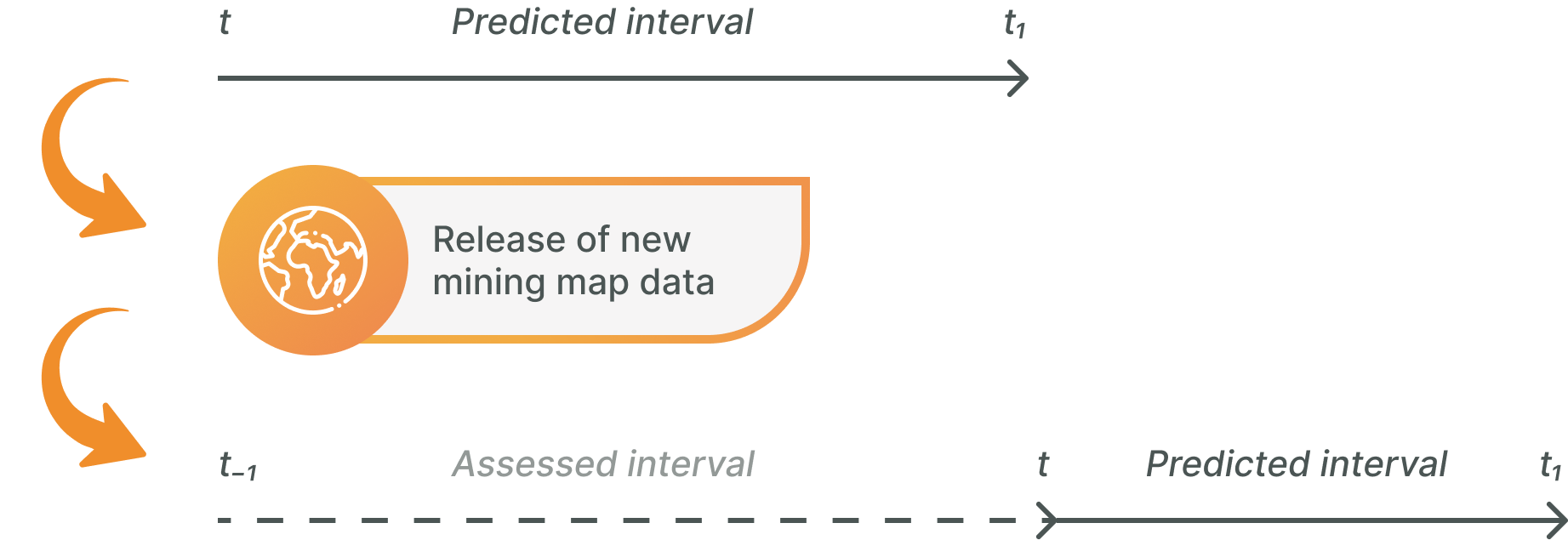

Predicted interval

The predicted interval was created to find a solution for estimating Bitcoin's ann. GHG emissions daily, even in the absence of mining map data for the period between the most recent data point and the current date in instances where these are not the same, as illustrated in Figure 2. This issue arises because of the different frequencies with which the required data is published, which can lead to an information gap between the latest available data on hashrate distribution and that available on electricity consumption.

While Bitcoin's estimated ann. electricity consumption is published daily, data on geographical hashrate distribution is published infrequently. This means that when calculating the most current estimate of ann. Bitcoin GHG emissions, mining map data is usually unavailable while an estimate on ann. electricity consumption is.

The above assumption solves this problem by assuming the most recent mining map data available is an accurate approximation of the current hashrate distribution. Thus, an estimate of ann. GHG emissions can still be calculated daily, even if the actual hashrate distribution is unknown at that time. This implies that if, for instance, mining map data is available until date t, but the current date is t1, the geographical hashrate distribution of date t is used as a proxy for the period between the two dates for which data is unavailable.

As shown in Figure 4, after new mining map data has been released, t shifts to the right and represents the month for which the latest data is available. The availability of this new data means the GHG emission estimates of the previously predicted interval must be retroactively adjusted and hence become part of the assessed interval. Therefore, the data points in the predicted interval should be viewed with caution, as they are revised each time the mining map is updated to include data from months that were previously not recorded.

Figure 4: The shift from the predicted interval to assessed interval after the release of new mining map data

In the predicted interval, ann. GHG emissions (Gd) are estimated by multiplying the ann. total Bitcoin electricity consumption (Ed) by the latest available emission intensity (It) in the assessed interval, as illustrated in Equation 19.

The latest available emission intensity (It) is derived by dividing the ann. GHG emission estimate at date t by the ann. total Bitcoin electricity consumption estimate at date t, as illustrated in Equation 20. To reiterate, date t represents the last day for which mining map data was available, and, thus, the latest available emission intensity estimate is also at date t.

Limitations of the model

Since our estimate of Bitcoin's GHG emissions is based on previous research on Bitcoin electricity consumption and mining map data, the respective assumptions and limitations of both data sources are also inherited. In addition, a set of new assumptions and limitations have been introduced, specific to determining GHG emissions.

As mentioned in the summary, this study addresses the environmental impact resulting from the use of dedicated mining hardware, i.e., the emissions caused by the electricity consumption required to operate the equipment. (A more detailed explanation of what this comprises can be found on our website.) Therefore, this study cannot be considered a life-cycle assessment. Furthermore, for simplification, we assume that marginal emissions equal average emissions, meaning that the emission intensity (in terms of gCO2e/kWh) of a given location is not influenced by any additional demand created by Bitcoin mining operations. Below is a brief overview of key assumptions carried over from previous studies.

Electricity demand is greatly influenced by electricity rates. For this study, we have used the default average electricity cost per kilowatt-hour, given on our website. Other costs are not considered. Another crucial parameter that determines electricity consumption is the average efficiency of the mining hardware.

Besides electricity demand, the location of Bitcoin mining operations is of utmost importance. As outlined in the dedicated methodology section, creating the mining map depends on a sufficiently large sample size and the non-existent or insignificant use of VPNs or proxy services by Bitcoin miners.

In addition to the assumptions and limitations inherited from previous studies, estimating GHG emissions required introducing a new set of assumptions, which include the following:

The median GHG emission intensities given in Table 3 represent all countries belonging to one of the four categories listed in Table 4.

The world electricity mix is a fair approximation if there is no available mining map or country-specific data, or if a country has been flagged as an anomaly (Appendix 2). Because there is ample anecdotal evidence of seasonal relocations of mining operations in China before mining map data was available, we conducted a test to examine how accounting for these relocations would affect cumulative emissions in the historical interval. We found that our chosen method (of using the world electricity mix) would slightly overestimate cumulative emissions during this period by 2.96 MtCO2e if these relocations occurred before they were captured in our dataset. A more detailed description of the analysis performed can be found in Appendix 3.

The most recent update of the mining map is a fair approximation of the current global Bitcoin network hashrate distribution.

When data is available, it is assumed that the electricity generation mix of a country, province or state is also representative of Bitcoin mining in that region.

The province-specific electricity generation data of Sichuan, Yunnan, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Beijing, Gansu, Qinghai and Shanxi fairly represents the electricity mix used by Bitcoin miners in each of those provinces. For ‘other provinces’, China's national data is assumed to be a fair representation.

It is assumed that the amount of electricity demanded by Bitcoin miners remains constant throughout the day and the accessed electricity mix does not vary between daytime and night-time.

Our estimates do not account for any activities that could reasonably be expected to reduce emissions, such as using flare-gas, off-grid (behind the meter) Bitcoin mining, waste heat recovery or carbon offsetting. Currently, there is little reliable data on these activities, but we are working to incorporate these factors into future versions of the CBECI.

While most limitations do not have a major impact on the performance of the model, we are aware of its imperfections. The CBECI is an ongoing project that is maintained and refined continuously in response to changing circumstances, with all changes being transparently highlighted in the Change Log.

If you would like to suggest how we could improve the index, please feel free to send us a message.

How does our estimate compare to other estimates?

In the past, there have been multiple attempts to analyse Bitcoin's environmental footprint. However, except for the estimate provided by Digiconomist, there is no live index tracking emissions in real time. We would like to point out that emission estimates vary significantly over time, therefore, when comparing emission estimates from different studies, the date of publication should be considered. Moreover, the only GHG considered in some estimates is carbon dioxide (CO2). A non-exhaustive list of available studies and articles is presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Available studies and articles on Bitcoin's environmental footprint

Author(s) | Publication date | Title | Estimate in MtCO2(e) | Approach |

Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance | Live | Greenhouse Gas Emissions Index | Updated daily; estimate in CO2e | |

de Vries, A. | Live | Emissions estimate in CO2; updated daily | ||

de Vries, A., Gallersdörfer, U., Klaaßen, L., & Stoll, C. | 02/2022 | Revisiting Bitcoin’s carbon footprint

| 65.4 | Emissions estimate in CO2 |

Coinshares | 01/2022 | 39 | Emissions estimate in CO2e; adjusted for flare mitigation | |

Sandner P., Lichti C., Heidt C., Richter R., Schaub B. | 08/2021 | The Carbon Emissions of Bitcoin From an Investor Perspective | 37.97 | Emissions estimate in CO2e |

Köhler S., Pizzol M. | 11/2019 | 17.29 | Emissions estimate in CO2e | |

Stoll, C., KlaaBen, L., & Gallersdörfer, U. | 06/2019 | 22.0–22.9 | Emissions estimate in CO2 |

Appendix

Appendix 1: Countries and jurisdictions in category 1

Philippines | Turkmenistan | Angola | Bangladesh |

Ghana | Croatia | Slovenia | Seychelles |

New Zealand | Iraq | Qatar | Costa Rica |

Denmark | Israel | Japan | Saudi Arabia |

Belgium | World | Montenegro | Finland |

Lebanon | Syrian Arab Republic | Vietnam | Albania |

Zimbabwe | Slovakia | Argentina | Australia |

Bahrain | Jordan | Tajikistan | Nepal |

Jamaica | Cambodia | Kenya | Mozambique |

Cyprus | Congo, Dem. Rep. | British Virgin Islands | Nicaragua |

Tunisia | Sri Lanka | Lesotho | Ecuador |

Afghanistan | Bolivia | Luxembourg | Uruguay |

Morocco | Cameroon | Malawi | Panama |

Chile | Pakistan | Nigeria | Uganda |

Algeria | Guatemala | Sweden | Italy |

Hungary | Romania | Kuwait | United Arab Emirates |

Trinidad and Tobago | Taiwan, China | Brunei Darussalam | Ethiopia |

United Kingdom | Netherlands | Uzbekistan | Iceland |

France | Mongolia | Armenia | Kyrgyz Republic |

Thailand | Paraguay | Ukraine | Georgia |

Venezuela, RB | Norway | Canada | Libya |

Kazakhstan | Iran, Islamic Rep. | Malaysia | India |

South Africa | Mexico | Russia | Switzerland |

Czechia | Dominican Republic | Poland | Bhutan |

Belarus | Portugal | Greece | Hong Kong SAR, China |

Austria | Egypt, Arab Rep. | Bulgaria | North Macedonia |

Indonesia | Lithuania | Serbia | Lao PDR |

Peru | Latvia | Spain | Azerbaijan |

Turkey | Brazil | Estonia | Colombia |

Bosnia and Herzegovina | Moldova | Palestine | Cuba |

Korea, Rep. | El Salvador | Suriname | Botswana |

Niger | Yemen | Mauritius | Malta |

Puerto Rico | Benin | Mali | Senegal |

Belize | Zambia | Honduras | Tanzania |

Namibia | Oman | Togo | Central African Republic |

Madagascar | Tonga | Fiji | Congo |

Sudan | Burundi | Antigua and Barbuda | Guinea |

Barbados | French Polynesia |

|

|

Appendix 2: Countries and jurisdictions in category 4

Country | Reason |

Germany | Anomaly |

Ireland | Anomaly |

Gibraltar | No data available |

Niue | No data available |

Saint Helena | No data available |

Western Sahara | No data available |

Bermuda | No data available |

Singapore | Anomaly |

Kosovo | No data available |

Andorra | No data available |

Côte d'Ivoire | No data available |

Curacao | No data available |

Macau SAR, China | No data available |

Liechtenstein | No data available |

Appendix 3: Analysing the impact of seasonal relocations within China before data was available, based on dynamics observed in 2020

Anecdotal evidence suggests that seasonal relocations of Bitcoin miners in China occurred before September 2019, the start of our assessed interval. As a result, our current approach does not take these relocations into account as, during this period, we assume that the Bitcoin network hashrate is distributed as per the historical interval and, hence, uses the world electricity mix. Therefore, we attempted to determine the extent to which cumulative emissions (in MtCO2e) would differ if we accounted for these regional dynamics in China before they were captured in our data. To account for seasonal shifts within China before this data was available, we used the observed regional dynamics in 2020 (see Table A1) as a guide to how the hashrate was distributed within China over the course of a year. Data from 2020 was used because it was the only period for which data was available from January to December.

Table A2 shows how the Bitcoin network hashrate was distributed between China and the rest of the world. For the latter’s hashrate share, we assume that the world electricity mix is representative. In Figure A1, the red bars show the months in which our chosen approach resulted in overestimated GHG emissions, while the green bars represent the months in which GHG emissions were underestimated. Overall, we found that the cumulative emissions from 18 July 2010 to 31 August 2019 would be slightly overestimated (by 2.96 MtCO2e) if the seasonal relocations actually occurred before the data was available and the 2020 dynamics were assumed to be representative.

Figure A1: Historical simulation

Table A1: Assumed hashrate distribution within China based on 2020 data

Month | Sichuan (in %) | Xinjiang (in %) | Yunnan (in %) | Inner Mongolia (in %) | Gansu (in %) | Beijing (in %) | Shanxi (in %) | Qinghai (in %) | Other provinces (in %) |

January | 16.7 | 49.5 | 8.3 | 11.4 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 6.7 |

February | 15.4 | 51.5 | 8.6 | 11.8 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 5.7 |

March | 14.7 | 55.6 | 8.3 | 12.5 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 4.6 |

April | 14.9 | 55.2 | 8.4 | 12.5 | 0.8 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 4.2 |

May | 26.4 | 35.7 | 11.7 | 10.8 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 11.1 |

June | 43.4 | 27.3 | 12.4 | 5.6 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 6.4 |

July | 52.7 | 19.8 | 14.7 | 6.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 4.2 |

August | 50.5 | 17.3 | 16.8 | 4.1 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 4.3 |

September | 61.1 | 9.6 | 14.9 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 5.1 |

October | 51.8 | 13.0 | 14.7 | 11.1 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 9.6 |

November | 24.1 | 33.3 | 17.2 | 14.3 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 8.0 |

December | 12.6 | 46.4 | 11.4 | 17.2 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 8.1 |

Table A2: Assumed historical global hashrate distribution and emission intensities

Date | China | China | Rest | Rest of the world | World |

07/2010 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 554.12 | 417.53 |

08/2010 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 554.12 | 418.69 |

09/2010 | 67.1 | 298.78 | 32.9 | 554.12 | 382.74 |

10/2010 | 67.4 | 355.06 | 32.6 | 554.12 | 420.01 |

11/2010 | 55.6 | 509.88 | 44.4 | 554.12 | 529.53 |

12/2010 | 53.3 | 619.47 | 46.7 | 554.12 | 588.93 |

01/2011 | 72.7 | 619.54 | 27.3 | 562.26 | 603.89 |

02/2011 | 73.0 | 628.03 | 27.0 | 562.26 | 610.25 |

03/2011 | 67.1 | 640.22 | 32.9 | 562.26 | 614.54 |

04/2011 | 64.8 | 640.15 | 35.2 | 562.26 | 612.74 |

05/2011 | 59.5 | 529.78 | 40.5 | 562.26 | 542.94 |

06/2011 | 64.7 | 371.95 | 35.3 | 562.26 | 439.18 |

07/2011 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 562.26 | 420.23 |

08/2011 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 562.26 | 421.39 |

09/2011 | 67.1 | 298.78 | 32.9 | 562.26 | 385.42 |

10/2011 | 67.4 | 355.06 | 32.6 | 562.26 | 422.66 |

11/2011 | 55.6 | 509.88 | 44.4 | 562.26 | 533.15 |

12/2011 | 53.3 | 619.47 | 46.7 | 562.26 | 592.74 |

01/2012 | 72.7 | 619.54 | 27.3 | 558.96 | 602.99 |

02/2012 | 73.0 | 628.03 | 27.0 | 558.96 | 609.36 |

03/2012 | 67.1 | 640.22 | 32.9 | 558.96 | 613.45 |

04/2012 | 64.8 | 640.15 | 35.2 | 558.96 | 611.58 |

05/2012 | 59.5 | 529.78 | 40.5 | 558.96 | 541.60 |

06/2012 | 64.7 | 371.95 | 35.3 | 558.96 | 438.01 |

07/2012 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 558.96 | 419.14 |

08/2012 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 558.96 | 420.29 |

09/2012 | 67.1 | 298.78 | 32.9 | 558.96 | 384.33 |

10/2012 | 67.4 | 355.06 | 32.6 | 558.96 | 421.58 |

11/2012 | 55.6 | 509.88 | 44.4 | 558.96 | 531.68 |

12/2012 | 53.3 | 619.47 | 46.7 | 558.96 | 591.19 |

01/2013 | 72.7 | 619.54 | 27.3 | 559.91 | 603.25 |

02/2013 | 73.0 | 628.03 | 27.0 | 559.91 | 609.62 |

03/2013 | 67.1 | 640.22 | 32.9 | 559.91 | 613.77 |

04/2013 | 64.8 | 640.15 | 35.2 | 559.91 | 611.91 |

05/2013 | 59.5 | 529.78 | 40.5 | 559.91 | 541.99 |

06/2013 | 64.7 | 371.95 | 35.3 | 559.91 | 438.35 |

07/2013 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 559.91 | 419.45 |

08/2013 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 559.91 | 420.60 |

09/2013 | 67.1 | 298.78 | 32.9 | 559.91 | 384.65 |

10/2013 | 67.4 | 355.06 | 32.6 | 559.91 | 421.89 |

11/2013 | 55.6 | 509.88 | 44.4 | 559.91 | 532.10 |

12/2013 | 53.3 | 619.47 | 46.7 | 559.91 | 591.64 |

01/2014 | 72.7 | 619.54 | 27.3 | 554.53 | 601.78 |

02/2014 | 73.0 | 628.03 | 27.0 | 554.53 | 608.16 |

03/2014 | 67.1 | 640.22 | 32.9 | 554.53 | 612.00 |

04/2014 | 64.8 | 640.15 | 35.2 | 554.53 | 610.02 |

05/2014 | 59.5 | 529.78 | 40.5 | 554.53 | 539.81 |

06/2014 | 64.7 | 371.95 | 35.3 | 554.53 | 436.45 |

07/2014 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 554.53 | 417.67 |

08/2014 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 554.53 | 418.82 |

09/2014 | 67.1 | 298.78 | 32.9 | 554.53 | 382.88 |

10/2014 | 67.4 | 355.06 | 32.6 | 554.53 | 420.14 |

11/2014 | 55.6 | 509.88 | 44.4 | 554.53 | 529.71 |

12/2014 | 53.3 | 619.47 | 46.7 | 554.53 | 589.13 |

01/2015 | 72.7 | 619.54 | 27.3 | 542.05 | 598.37 |

02/2015 | 73.0 | 628.03 | 27.0 | 542.05 | 604.79 |

03/2015 | 67.1 | 640.22 | 32.9 | 542.05 | 607.88 |

04/2015 | 64.8 | 640.15 | 35.2 | 542.05 | 605.63 |

05/2015 | 59.5 | 529.78 | 40.5 | 542.05 | 534.75 |

06/2015 | 64.7 | 371.95 | 35.3 | 542.05 | 432.04 |

07/2015 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 542.05 | 413.53 |

08/2015 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 542.05 | 414.69 |

09/2015 | 67.1 | 298.78 | 32.9 | 542.05 | 378.77 |

10/2015 | 67.4 | 355.06 | 32.6 | 542.05 | 416.07 |

11/2015 | 55.6 | 509.88 | 44.4 | 542.05 | 524.17 |

12/2015 | 53.3 | 619.47 | 46.7 | 542.05 | 583.29 |

01/2016 | 72.7 | 619.54 | 27.3 | 533.73 | 596.10 |

02/2016 | 73.0 | 628.03 | 27.0 | 533.73 | 602.54 |

03/2016 | 67.1 | 640.22 | 32.9 | 533.73 | 605.15 |

04/2016 | 64.8 | 640.15 | 35.2 | 533.73 | 602.70 |

05/2016 | 59.5 | 529.78 | 40.5 | 533.73 | 531.38 |

06/2016 | 64.7 | 371.95 | 35.3 | 533.73 | 429.10 |

07/2016 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 533.73 | 410.78 |

08/2016 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 533.73 | 411.93 |

09/2016 | 67.1 | 298.78 | 32.9 | 533.73 | 376.04 |

10/2016 | 67.4 | 355.06 | 32.6 | 533.73 | 413.35 |

11/2016 | 55.6 | 509.88 | 44.4 | 533.73 | 520.48 |

12/2016 | 53.3 | 619.47 | 46.7 | 533.73 | 579.41 |

01/2017 | 72.7 | 619.54 | 27.3 | 529.88 | 595.05 |

02/2017 | 73.0 | 628.03 | 27.0 | 529.88 | 601.50 |

03/2017 | 67.1 | 640.22 | 32.9 | 529.88 | 603.87 |

04/2017 | 64.8 | 640.15 | 35.2 | 529.88 | 601.34 |

05/2017 | 59.5 | 529.78 | 40.5 | 529.88 | 529.82 |

06/2017 | 64.7 | 371.95 | 35.3 | 529.88 | 427.74 |

07/2017 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 529.88 | 409.50 |

08/2017 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 529.88 | 410.65 |

09/2017 | 67.1 | 298.78 | 32.9 | 529.88 | 374.77 |

10/2017 | 67.4 | 355.06 | 32.6 | 529.88 | 412.10 |

11/2017 | 55.6 | 509.88 | 44.4 | 529.88 | 518.76 |

12/2017 | 53.3 | 619.47 | 46.7 | 529.88 | 577.61 |

01/2018 | 72.7 | 619.54 | 27.3 | 526.44 | 594.11 |

02/2018 | 73.0 | 628.03 | 27.0 | 526.44 | 600.57 |

03/2018 | 67.1 | 640.22 | 32.9 | 526.44 | 602.74 |

04/2018 | 64.8 | 640.15 | 35.2 | 526.44 | 600.13 |

05/2018 | 59.5 | 529.78 | 40.5 | 526.44 | 528.43 |

06/2018 | 64.7 | 371.95 | 35.3 | 526.44 | 426.53 |

07/2018 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 526.44 | 408.36 |

08/2018 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 526.44 | 409.51 |

09/2018 | 67.1 | 298.78 | 32.9 | 526.44 | 373.64 |

10/2018 | 67.4 | 355.06 | 32.6 | 526.44 | 410.98 |

11/2018 | 55.6 | 509.88 | 44.4 | 526.44 | 517.24 |

12/2018 | 53.3 | 619.47 | 46.7 | 526.44 | 576.00 |

01/2019 | 72.7 | 619.54 | 27.3 | 512.79 | 590.38 |

02/2019 | 73.0 | 628.03 | 27.0 | 512.79 | 596.88 |

03/2019 | 67.1 | 640.22 | 32.9 | 512.79 | 598.25 |

04/2019 | 64.8 | 640.15 | 35.2 | 512.79 | 595.33 |

05/2019 | 59.5 | 529.78 | 40.5 | 512.79 | 522.90 |

06/2019 | 64.7 | 371.95 | 35.3 | 512.79 | 421.70 |

07/2019 | 66.9 | 349.82 | 33.1 | 512.79 | 403.83 |

08/2019 | 66.9 | 351.55 | 33.1 | 512.79 | 404.99 |